|

| Penguin Classics Edition of Kipling's Kim Image from Amazon.com |

When I first read, rather tried to read, Rudyard Kipling's Kim in graduate school I felt I had met my match. Although this was the book that was widely considered to be Kipling's masterpiece I couldn't believe it at the time.

I found that Kipling's book of high adventure during the height of British power in India to be a dull, prodding affair, especially in the earlier chapters. I found myself in the same position as Kim, the young title character, and his lama (read: not llama), looking for enlightenment in some way.

When I was in grad school, I read enough criticism, did enough background research, and read enough of the book to write a decent response essay highlighting the main ideas and themes behind the book. I managed my way through my class discussion. And yet, after all this, I knew I had not conquered Kipling's book.

Part of what turned me off of Kipling's book initially was the fact that the author has been trailed in history by a somewhat morally reprehensible past, that is inescapable, but not always helpful in judging a work of literature, initially. My only familiarity with Kipling in grad school came from having earlier read his poem, "The White Man's Burden," which smacked of all kinds of racism, cultural dominance, and Social Darwinism. Not exactly admirable traits in a writer.

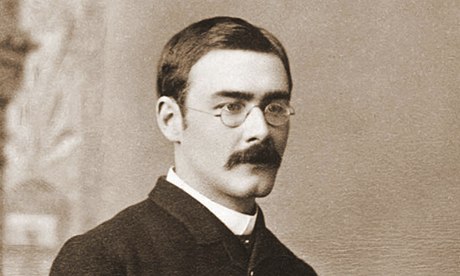

|

| Kipling, a writer not without edges. Image from theguardian.com |

Edward Said, author of Orientalism, had a scathing view of Kipling's Kim at the end of the book. In Said essay, he highlights all the ills of British Colonialism in India. Boiled down in essence, Said posits the British citizens believed they were destined and entitled to rule, and as such, believed they were better than all races, including Indians.

This was the world in which Kipling penned Kim, the story of a young, orphaned British boy who goes on a quest with a lama to find a sacred river in the northern reaches of India. The lama believes that finding the river is essential in reaching his enlightenment. The boy simply wants adventure. At times Kim believes the old man's quest to find the sacred river a little crazy, but follows nonetheless, partly born out of a sense of deep compassion and respect for the withered spiritualist. It is here that Kipling's powers as a writer shine through.

Apart from the undertones of racism (on all sides) that run through the book, Kipling's message, story, quest, etc. has a lot heart and remains timeless. That timeless nature is evident is the book, where the lama tells the boy that life is like a "Wheel" that goes around and around. Enlightenment releases you from the wheel, but only for those wise enough to find it. A late scene in the book has Kim coming face to face with a woman who lost her son, an irony not lost on the reader, since the boy lost his parents. This is a great example of the wheel coming to play in the story, as both philosophy and motif. Pain, desire, struggles, loss, and happiness are all part of the "Wheel" and are part of life.

At the books end, the two find the river, and the lama beckons Kim to join him in his enlightenment. The book ends in a somewhat obscure, open-ended manner. Kim doesn't really believe in the concept of enlightenment, but the lama says, "Come!" and join him, as if enlightenment is his for the taking. He need only walk the path.

By the novel's end, I'm not sure if I fully reached enlightenment, but I definitely feel I have a deeper appreciation and understanding for Kipling's work.

No comments:

Post a Comment